Four years ago, I made a strange decision for my health.

I decided to go and look at more paintings.

I did not change my diet. I did not join a gym. I simply told myself: “See more art. See it in real life.”

So I went to museums. I walked through long halls. I stood in front of big famous works. I looked. I nodded. Sometimes I even felt “wow” for a moment.

But something was wrong.

I was looking, yet I was not really seeing.

After a few minutes, every painting turned into another blur in my head. I forgot the names. I forgot the scenes. I did not understand what I was looking at. I felt tired, not touched.

It started to bother me.

I thought, “I am surrounded by all this beauty and history. Why do I feel almost blind?”

The advice that changed how I look

I asked a friend who knows a lot about art, “What should I do? How can I see paintings better?”

His answer was simple.

He said, “Stop chasing painters and styles. Look for scenes.”

“Pick a story,” he said.

“Learn that story. Then go and see how different artists painted that same moment: that king, that murder, that battle, that miracle.”

Do not start with “Who is the artist?” or “Is this Baroque or Renaissance?”

Start with: “What is happening here?”

Who is about to die? Who is betraying whom? What is changing forever in this moment?

That one suggestion changed everything for me.

I stopped walking quickly from one painting to the next. I chose a few big scenes from history and religion. Then I searched for them in different museums, in different times, on different walls.

And I noticed something important.

The scene is the same.

The story is the same.

The way each painter tells it is completely different.

The painting is not only a picture.

It is an opinion. A feeling. A choice.

Once I saw this, paintings opened up. They stopped being “nice old images” and started to feel like living conversations about power, fear, courage, betrayal, and faith.

Why murder scenes matter

For this practice, I chose a hard group of scenes.

Assassinations.

Moments where one person kills another person who holds huge power. A king. A general. A prophet. A ruler.

These scenes are often turning points in history.

A world ends. A new world begins.

Most of these paintings were made in times when there were no cameras, no films, not even cheap printed images. Many people could not read or write. Painting was one of the main ways to “record” reality and pass on stories.

So when a painter chose to show a murder, they were doing more than showing blood. They were saying:

“This is how I see this event.”

“This is who I think is right, who is wrong, who is tragic, who is noble.”

Let me share a few of these scenes with you, not as an art expert, but as a curious person who is trying to learn how to see.

Julius Caesar: before, during, after

The first scene is maybe the most famous assassination in Western history.

The murder of Julius Caesar.

Caesar is not yet an emperor, but he is close. He is a very powerful general in Rome. He has won many wars. People love him. The Senate fears him. There is a special role in Rome called “dictator” where one person gets all the power for a short time in an emergency. Caesar wants to stay in this role longer. Some think he wants to turn the Republic into a kingdom.

A group of senators decide that if they want to save the Republic, they must kill Caesar.

This moment has been painted many times. When I started to look for it, I saw three kinds of scenes.

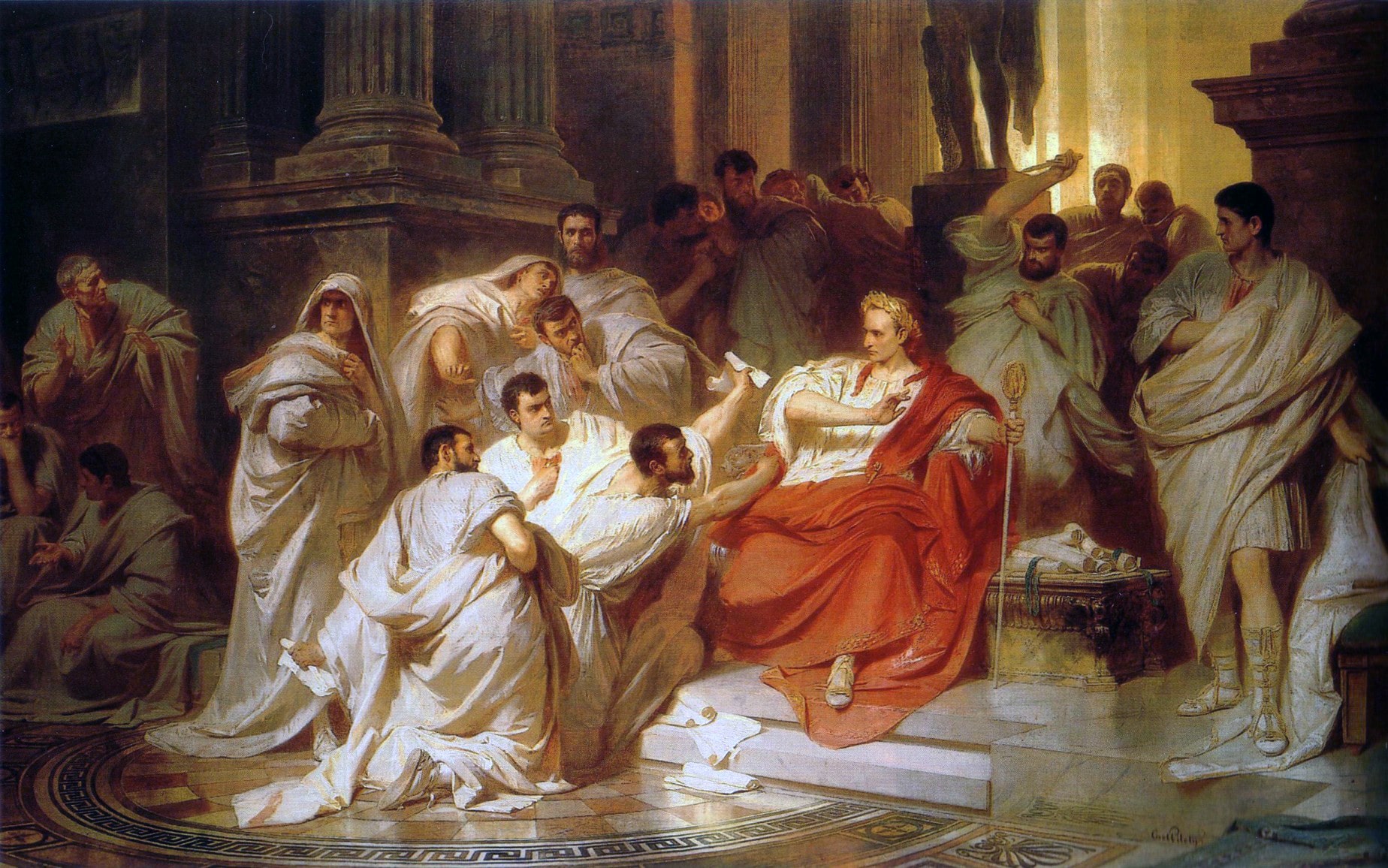

1) The moment before the first stab

In one painting, Caesar is still alive. He is sitting on his chair in the Senate. Around him stand the men who are about to kill him. The light falls on his bright robe, so your eye goes to him first.

His face looks calm but also a little confused.

He thinks he is safe. He thinks he is among friends.

If you look at the others, you see hidden hands, nervous eyes, strange body positions. One man pulls his robe in a way that looks like respect, but this gesture is actually the secret signal: “Now we start.”

The room looks like a normal meeting of senators, but the air is heavy with fear. Some men look ready to stab. Others look like they are asking themselves, “Are we really going to do this?”

From this painting I learned to ask:

Who thinks they are safe here?

Who knows they are in danger?

Who is pretending?

Suddenly, it is not only a history lesson. It is a human moment I can feel.

2) The moment of betrayal

In another painting, we jump a few seconds forward.

The knives are out. Caesar is wounded. The key moment is when he sees the face of Brutus, the friend he trusted, among the attackers.

This is the famous line from Shakespeare, “Et tu, Brute?” — “You too, Brutus?”

In this painting, the hurt is not only in his body. It is in his eyes.

He is not only asking, “Why are you killing me?” He is also asking, “How could you, of all people, join them?”

The painting almost forces me to ask a question that people still debate after 2,000 years:

Was Brutus right?

If they killed Caesar to save the Republic from turning into an empire, and Rome became an empire anyway, what did this murder really change?

Here, the painting is doing more than showing a crime.

It is asking a political and moral question.

Was this killing necessary?

Or was it a tragic mistake?

3) The silence after the crime

A third painting shows the scene after everything is over.

Caesar’s body lies on the floor. The great hall of Rome is almost empty. The killers walk away in the distance, some with raised swords. The huge marble columns and stairs are calm and still.

There is no blood splashing. No dramatic movement. Only cold, clean stone and a small dead body.

The message I feel is simple and heavy:

Power passes.

Bodies fall.

The building remains.

Looking at these three paintings together taught me a small skill:

When I see any image now, even on social media, I ask myself:

Where are we in the story?

Before the act, in the middle of the chaos, or in the silence after?

Each point in time tells a different truth.

Judith and Holofernes: the woman who changed a war

The second scene comes from a religious story.

The city is under siege from a foreign army led by Holofernes. Inside the walls, fear rules. Judith decides to act.

She dresses beautifully, walks to the enemy camp, charms Holofernes into letting down his guard, and when he is drunk and asleep, she beheads him. She brings the head back; the city’s fear turns to courage.

Painters show very different Judiths.

- In some, she hesitates—soft face, almost sad; the maid is practical.

- In others, she is focused and strong; both women act; the blood is visible and hard to look at.

One woman painter who took on this scene had survived violence and spoke about it in court. Her Judith is not fragile. She has cried enough and is ready to act.

Question learned: How does this painter see women and power?

Same story, changing woman—revealing the painter’s world.

Salome and John the Baptist: the dance and the head

The third scene: a prophet’s beheading.

John the Baptist speaks truth to power and is jailed. At a party, Salome dances so well the ruler vows to grant any wish. On her mother’s advice, she asks for John’s head on a tray.

In one church painting, three figures emerge from darkness: Salome with a tray, the executioner, an older woman.

It reads like a document: here is what happened. Quiet, heavy, almost no background.

Another painter places Salome in a vast jeweled palace—beauty over horror. If you know the story, dread grows; the terror is in the context, not the surface.

New question: What part of the story is this painting hiding?

The blood? The prophet? The guilt? Sometimes what’s unseen is louder.

Learning to see like this in everyday life

Why does this matter?

Because this practice trains four human skills at once:

- Critical thinking — what’s shown or hidden, and why?

- Empathy — feel each person’s position.

- Imagination — stand inside the room.

- Storytelling — one event becomes many stories depending on who tells it.

Now, with news photos or clips, I ask:

- Where are we—before, during, after?

- Who is lit, who is in the dark?

- Whose pain fills the frame, whose is outside it?

- Who looks noble or small, and who decided that?

Images stop controlling me. I start to question them.

A small invitation

You do not need names, dates, or “art world” language. You need curiosity.

Next time:

- Pick one scene.

- Learn its story.

- Find three versions of that same moment.

- Look slowly and ask:

- What is happening here, in one sentence?

- Who looks powerful, who looks powerless?

- Where do I feel the strongest emotion?

- If I stood inside this space, where would I be?

You will remember more, understand more, enjoy more.

I started because I wanted to “see more paintings.”

Now I feel something deeper.

I am learning, little by little, how to see.